“In this hospital death dances around my bed at night.”

—Frida Kahlo

I am standing in front of the bed where Frida Kahlo died, absorbing the beauty of her petite Mexican death mask, shrouded in a green and gray rebozo, touching her flamboyantly painted and glowing corset. My tears flow and a tremendous sadness I have been experiencing, while moving around Casa Azul, flood me.

I recall her statement to her young lover, Alejandro Gomez Arias after her tragic streetcar accident. “…. death dances around my bed at night.” (Herrera, 2002, p. 36) I see the dance of death move around this bed of suffering, from her tragic accident, numerous operations and physical anguish, miscarriages, love affairs, and her political as well as cultural pain. The words of Octavio Paz, a Mexican writer, capture me again, “…. Mexicans have no qualms about getting close and personal with death.” (Paz, 1961 p. 75). By becoming close and personal with Frida’s suffering, life and death, I become close to my experience of death again. Remembering my encounters with death both literal and symbolic, I recalled my first dreams of Frida after my own series of miscarriages.

Twenty years ago, I did not understand my dreams of Frida in which we share our suffering about infertility. Curious, I went back to Frida’s biography I had read ten years prior to my dreams. My unconscious had remembered Frida’s suffering around her own infertility. Twenty years ago, Frida spoke to me in my dreams to comfort me and guide me back to my creative resource of painting. Inspired by Frida, I painted my pain.

Standing here in Casa Azul, now as an older woman, I find she moves me again. I traveled to Mexico in a pilgrimage to heal from a current major life disappointment. I recalled Jung’s words that helped me hold this perceived failure. “The experience of the self is always a defeat of the ego” (CW, vol. 14, par. 778, p. 546).

Living so closely with pain, loss, disappointment and death, Frida’ life and art embody Jung’s words for me. Kahlo’s dance with death is a vivid portrait of how our unwanted agonies can be our greatest teachers. Frida’s paintings became the voice of her psyche.

For Frida, life and death existed simultaneously. She understood the archetype of death most intimately, as it was palpable everyday. With death as her guide, she plunged into her internal world through her art. This descent allowed her to ultimately value her life, her culture, and her inner-directed creative expression. Frida’s images penetrate into this paradox of existence, the dance of life and death. Invited into her world, she seduces us to confront similar issues in our own lives. Frida has become a mesmerizing archetypal image of the wounded and triumphant feminine: the feminine whose teacher is her indigenous culture and death.

After experiencing Casa Azul, I began to write seated in her garden. In my reverie, memories and images, as well as Jung’s reflections on death, cascaded through me. Vivid memories of my trip to Ghana come alive again, teaching me about death through their funeral rituals. After this trip eight years ago, I realized how much death was interwoven in my life. I was born into my family’s death dance with the death of my three of grandparents during the first year of my life. My internal terrain was altered forever. Eight years ago, I felt compelled to understand my own death dance. I turned to anthropology, theology, archeology, and Jung’s reflections on death to help me understand its meaning (Metcalf & Huntington, 1991, Yates, 1999). Jung reflected the Ghanaian and the Mexican as well as my own budding sense of the importance of death. “Death is psychologically as important as birth, and, like it is an integral part of life” (CW, vol. 13, par 68, p.116).

Jung knew the archetypal importance of literal and symbolic death. He saw death as sacred marriage with life. Death is a universal wedding, which gives the soul wholeness.

“In light of eternity, it is a wedding, a mysterium conjunctionis. The soul attains, as it were its missing half, it achieves wholeness.”(Jung, 1961, p.314).

Delving deeper, Jung taught me how death informs life choices, especially marriage. Jung stressed the importance of confronting actual death as way of knowing the self, our values and the meaning of life. The symbolic aspect of death is equally important and speaks to us through our unconscious in dreams and imagery, highlighting the transformative aspects of symbolic death (Yates, 1999).

In my reverie that day in June, the power of Frida’s art become clearer to me. Frida’s art infuses Jung’s ideas with a flesh and blood experience of the Archetype of Death. Frida’s life and art openly confronts literal and symbolic death, pain and the shadow, all that we reject.

Frida took a stance in life that allowed her to live with her vulnerability and find strength and power by embracing what is rejected. Exploring the shadow of death was an integral part of her Mexican culture and provided a doorway to enter into the universal, the archetypal. Frida boldly painted her suffering, her relationship to death and all she was supposed to hide.

Frida’s art plays with these agonies. They become teachers of the paradox of existence. As she revealed her pain, she not only liberated herself, but liberated me, as well. Frida’s art gives us permission to embrace what is hard and difficult in our lives. Through her art and her psyche’s voice, creativity and meaning emerge from suffering and confrontations with the shadow of death.

Many scholars of Frida’s art feel she is guided by the Aztec goddess, Coatlique/Coatlicue, (pronounced kwat-lee-kweh), the Mother of the Gods,the goddess of life, death and rebirth, the Lady of the Skirt of Snakes. She is the Aztec goddess of death, dismemberment, and destruction as well as life. Coatlique wears a skirt of writhing snakes and a necklace made of human hearts, hands and skulls. Her feet and hands are adorned with claws and her breasts are depicted as hanging flaccid from nursing. She was created in the image of the “unknown,” the mystery created by the decorations of skulls, snakes, and lacerated hands (Granziera, 2005, p. 25). Coatlique is the archetypal symbol of death like the Hindu goddess Kali (Metcalf & Huntington, 1991, and West, 1997).

With skeletons and hearts in her paintings, Frida found a way not to fear Coatlique but to embrace her, thus finding meaning beyond suffering. With the help of this cultural icon, Frida understood symbolic death culturally as well as personally. This goddess will be her most profound instructor. With the help of Coatlique holding life and death, Frida’s ego can consciously contend with the unexpected appearance of the Self in her art and psyche.

Frida was challenged with many losses: her health, children, infidelity and constant physical suffering. The emergence of the self for Frida came from the loss of what the ego had embraced. Paraphrasing Jung, the ego’s desires may not be our path of individuation. But through symbolic death – loss, failure or illness – the Self can emerge surprisingly and unexpectedly.

Death’s presence compelled Frida to burrow into her internal world through her paintings. Little Frida wore the Mexican mask of death almost from birth. Her acknowledgment of death created a metamorphosis in her psyche, then in her art. Her confrontational paintings persuade us to explore these unknown territories in ourselves.

This piece of a beautiful 1922 poem by Frida speaks of her sorrow, perhaps due to the presence of the shadow of death following her.

“I had smiled nothing more. But clarity was in me and in the depth of my silence.

He followed me. Like my shadow, irreproachable and light.

In the night he wept a song….

He followed me.

I ended up crying, forgotten in the entrance of the Parish church

Produced by silk shawl, which soaked up my tears” (Herrera, 1991, p. 31).

These words captured my curiosity. They tell the story of her inner and outer life struggles. Lacing Frida’s art with Jung’s ideas gave me a deeper perspective on the archetype of death and the poignancy of her art and poetry. Now I more fully understand how Frida, the artist and poet, became an archetypal icon herself.

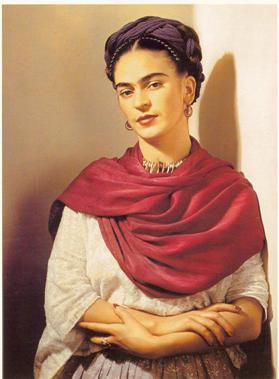

Frida was an immensely complex woman, but the following glimpses into her life and soul will illuminate the wisdom of her art. Magdalena Carmen Frieda Kahlo y Calderon was born on July 6, 1907 in Coyoacan, a suburb of Mexico City , to a Hungarian-Jewish father and a mother of Spanish and Mexican Indian descent.

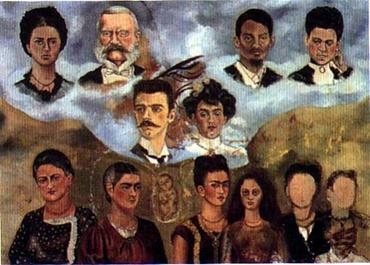

She was born and lived most of her life in Casa Azul in Coyoacan with her parents and four sisters, currently the home to the Frida Kahlo Museum . Her ancestral legacy and the family’s relationship to death are depicted in “My Family”. The dead and living exist together, but death seems to leave three images faceless.

Frida had vastly different relationships with her parents. Frida’s Mother, Matilde Calderon y Gonzalez, was still mourning the death of a son who had died shortly after birth when Frida was conceived. Perhaps Matilde had been suffering from postpartum depression as she was unable to breast-feed baby Frida. Soon after Frida’s birth, her mother became pregnant with her sister Christina. This may have deepened her mother’s depression and overwhelmed her. Frida felt unloved and abandoned by her mother and was competitive with her closest sister, Christina. This family photo illustrates the tone and feel of the family for little Frida laying in the chair on the left. The evidence of the mother complex is reflected in her face and body posture.

Of mixed Spanish and Mexican heritage, Matilde was a devout Catholic and seemed stern, self involved and distracted. It seemed that Frida did not receive, as Winnicott (1965) would say, the “good enough” mothering a young soul deserves. This inadequate mothering can leave a child unable to metabolize her experiences. These archetypal energies are left raw with no personal energy to humanize them. Fortunately, Frida had her art. She also had childhood’s natural connection to the archetypal realm through her imagination and art, which was paradoxically fueled by the woundings she experienced.

In “My Birth,” created after her mother’s death, Kahlo depicts the suffering she endured in her relationship with her mother. The baby is birthing herself, alone and unaided. On the wall is an image of the Virgin of Sorrows pierced by thorns, bleeding and weeping. This image seems to hold birth and death simultaneously. The mother wears a death’s shroud and the baby emerges with a face of anguish. Frida said this is “how I imagine I was born” (West, 1997, p.383); perhaps she felt she was born from a dead mother, a child’s experience of the depressed mother. (Carpenter, 2008, Herrera, 1983, 1991, and Zamora, 1990).

The collective mother gives Frida the nurturance she needs in “My nurse and I”. Frida was not breast-fed and experienced a wounded motherline, a mother complex (Lowinsky, 1992). She was forced to find the Great Mother through her culture, which she embraced in her Tehuana styled Mexican clothes, and through the universal mothering energies of her goddess, Coatlique. Frida started to create in this painting, the goddess and the mother she longed for and which will be developed in her later paintings. However, this nurse looks austere and has a pre-Hispanic death mask instead of a human face. Nurturance and life are laced with death and suffering as the baby Frida does not look securely held, nor does she have the soft maternal gaze that is so important in attachment and bonding (Schore, 2003).

Her fantasy and imagination allowed her to create the images she needed to metabolize her painful experiences and to live close to the collective. She contracted polio at the age of six, and it left her left leg thinner than the right. Frida had an imaginary friend who could dance, did not limp and who would be her friend when alone in bed. Frida talks about her friend in her diary:

“I must have been six years, when I experienced intensely an imaginary friendship with a little girl more or less the same age as me…I went down in great haste into the interior of the earth where my imaginary friend was always waiting for me (Kahlo, 1995, p. 230).

As an adult, this imaginary friend was transformed into her self-portraits, her empathetic mirroring and also into the “Two Fridas” as seen above. She is alone with herself, yet accompanies herself.

In “Frida in Coyoacan,” we see the younger Frida, alone, sad, yet perhaps prescient, knowing that tragedy waited to happen on the street of trolley tracks. Frida, with a knowing child’s face, communicates her close delicate connection to her personal and to the collective unconscious. The universality of death emerges through her dead mother, her polio, her suffering and her culture.

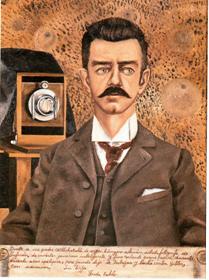

Fortunately and complicatedly, she had a positive and close relationship to her Father, Wilhelm Kahl, a German Jewish photographer who immigrated toMexico and changed his name to Guillermo Kahlo. He suffered from epilepsy and was a distant father: intellectual and introverted and solitary. Guillermo adored Frida and she idealized him. Frida identified with his creativity, intellect, and physical vulnerabilities.

Evelyn Torton Beck, a feminist scholar, (2006) delved into Frida’s paintings and journal as they revealed evidence of incest with her father, emotional or literal. This hypothesis about sexual wounding provides a fuller perspective on her behavior: Frida’s sexual acting out in adolescence, her marriage to an older man, Diego, and her affairs after the sexual betrayal by her sister, Christina which will be explored later.

Beck uses the surreal painting of “What the Water Gave Me” as evidence of her sexual wounding. These images, many from other painting here are fragmented into torturous and dangerous positions. This torture is reflected in the poetic passage from Frida’s Diary.

“Mine is a strange world

Of criminal silences

Of strangers’ watchful eyes

Misreading the evil.

Darkness in the daytime…

Was it my fault?

I admit, my great guilt

As great as pain

It was an enormous exit

Which my love went through”

(Kahlo, quoted in Beck, 2006. p. 77-78)

Her poignant words and disturbing imagery depict evil in a more collective, surreal context here, as well as her ability to hold paradox in her art. These paradoxes are held in a delicate balance that foreshadows a stronger resolution in her later pieces.

Jung felt that poetry helps us move into our dark currents and leads us to the collective unconscious. Frida’ artistry again embodies his words.

“(Poets) are always the first to divine the darkly moving mysterious currents and to express them, as best they can, in symbols that speak to us. They make known, like true prophets, the stirrings of the collective unconscious” (CW, vol. 6, par. 322, p.190).

Enacted incest, emotional or literal, is a soul murder to the feminine spirit and adds yet another possible death Frida experienced in her early years (Kalsched, 1996). This painting has special significance to me. When I visited the O’Gorman-designed home and studio of Frida and Diego in San Angel, I entered Frida’s tiny bathroom, and saw this piece “What the Water Gave Us” above her tub. I imagined her in this tub, wrestling with this soul murder through these sexual woundings, and discovering a creative resource to grapple with her inner death through her surreal imagery. Then I imagined her painting it in this very studio.

My photo of “What the Water Gave Us” taken at the San Angel, Frida and Diego’s second home and studio, 2005

As an adolescent, she identified with her Father, and often dressed as a male. There may have been many reasons, perhaps trying to replace the dead son and becoming the son her father might have wanted. However, the price of being the father’s daughter is high (Harding, 1970). There can be alienation from the feminine source of self. Frida did not identify with her mother and felt she was stupid. The seeds for difficulties in future relationships were planted: triangulation, betrayal and infidelity. These issues did pervade her love relationships and her relationship with her sister, Christina.

Tragedy laced her life. As mentioned, she struggled with polio as a child. With the encouragement of her father and her feisty personality, she overcomes her disability. Guillermo encouraged Frida to be physically active, pursue art and education. Paradoxically, Beck theorizes it was during this period of confinement and adoration that the emotional if not actual incest began.

This was the positive aspect of being the father’s daughter. Frida had the world of men opened to her and she developed a sense of androgyny, which would help her cope with her future tragedies. However, Frida may not have had a full sense of androgyny. She seemed to reject the personal feminine her mother offered, yet she found the feminine by embracing the Mexican culture through her Tehuana dress and artistic style.

There are moments that can change the course of our lives. Frida had such a life changing experience at the age of eighteen. While riding home from school, the bus she was on collided with a trolley car.

Frida sustained grave injuries which included a broken spinal column, a broken collarbone, broken ribs, a broken pelvis, eleven fractures in her right leg, a crushed and dislocated right foot and a dislocated shoulder (Alcantara and Egnolff, 2005, Herrera, 1983, 1991, Carpenter, 2008, Grimberg, 2006, and Zamora, 1991).

A broken handrail had entered her left hip and came out through her vagina. Frida joked it was in the accident she lost her virginity. Her sexuality was linked not only to sexual wounding, but also to physical suffering from these sexual injuries from the accident. Both pervaded her relationship with Diego Rivera, her future husband. During the accident, her clothes were torn from her body, the handrail impaled her, and a painter’s gold-leaf paint covered her bloody body. Many passersby called her “la bailarina, la bailarina,” the dancer (Herrera, 1991, p. 34).

She spent a year in bed recovering from these injuries. Told she would never walk again, Frida was determined, and did regain her ability to walk, but spent the rest of her life in constant pain, and had thirty-five surgeries, mostly on her back and right leg and foot. Frida, a Catholic, identified with Jesus and the sacredness of his horrible death and called this accident, “her Calvary” (Herrera, 1991, p. 37).

Coatlique dismembered Frida, and after this fragmentation. Frida was reborn again, first as a “mature, sad woman” (p.37) and second as icon of the wounded and triumphant feminine, that she holds for many women today.

In Frida’s words to her lover Alejandro Gomez Arias, she revealed the immensity of the accident in her life:

“… A little while ago, not much more than a few days ago, I was a child who went about in a world of colors, of hard and tangible forms. Everything was mysterious and something was hidden, guessing what it was, was a game for me. If you knew how terrible it is to know suddenly, as if a bolt of lightening illuminated the earth. Now I live in painful planet, transparent as ice, but it is as if I had learned everything at once in seconds. My friends, my companions become women slowly, I became old in instants and everything today is bland and lucid. I know that nothing lies behind, if there were something I would see it.” (p. 37).

Near death accidents, life threatening illnesses or the death of loved ones collapse life into a liminal space in which defenses are striped and all becomes a search for meaning, purpose and a spiritual attitude.

“The self…. hits consciousness unexpectedly, like lightning, and occasionally with devastating consequences. It thrusts the ego aside and makes room for a Superordinate factor, the totality of a person…” (CW, vol. 9, par. 541, p. 304).

Again embodying Jung’s words, the accident was life changing. She abandoned her hopes of pursuing a medical career and became a full time painter. This was a slow process. First, she painted her body casts and then her family created a bed-easel with a ceiling mirror over her reclining body. She stayed in her bed for the first year.

Having an essentially captive model, Frida drew and painted herself, and is best known for her self-portraits. Fifty-five of her 143 paintings are self-portraits. At first, her self-portraits were gifts to her boyfriend and friends. This seems to have been her way of ensuring their interest and love for her. By representing her face in a serene and impassive way, she was also attempting to deny the overwhelming feelings of helplessness and despair she felt. Just as she had done earlier, when she fell ill with polio, creating an imaginary double, she attempted to convey a sense of invulnerability, strength and transcendence over her body’s limitations.

Through her artistic empathetic mirroring, she is able to start metabolizing the horror she has experienced as well as embracing her inquisitive, irreverent and intellectual spirit.

Self–taught, at first her paintings were deliberately naïve and flattened forms of Mexican folk art, which she loved. As her paintings matured, she starkly painted her pain. She created sometimes shocking images of her numerous operations, painful miscarriages and her troubled marriage to Diego Rivera, symbolically depicting her physical as well psychological wounds.

As her individuation process deepened, her art changed. Her paintings became replete with bright colors and her indigenous Mexican imagery and culture, and her self-portraits trace her cultural embrace. These thorns, in “Self-portrait with Thorns,” pierce her neck as her face is surrounded by nature. There is no distance from her suffering in many of her later self-portraits. Frida experiences little deaths each day, but she is not cut off from nature. Frida is embraced by earth mother.

Frida was able to consciously hold the archetype of death without being overwhelmed by it. Her stance with death was interlaced with a Mexican cultural mythos of the Day of the Dead. In this mythos, one has close relationship with the spirit world. The spirits return to be fed when the veil is lifted between life and death on November 2nd, the Day of the Dead (Calavera, 2005).

Frida intrigues us with her metamorphosis on her canvases. In the transformative “Broken Columns,” Frida is no longer lying down as she was in life, but is upright and gazing into a reality that is beyond the personal, into the very nature of existence, an archetypal reality. Her ego consciousness can now hold her as a numinous symbol of the Self, the universal wounded and triumphant feminine. Frida stands tall and able to return to her life not in crisis, but with strength that her direct and inward gaze portrays as the objective Self (Alcantara and Egnolff, 2005, Herrera, 1983, 1991, Carpenter, 2008, Grimberg, 2006, West, 1997and Zamora, 1991).

At the age of 21, Frida fell in love with the Mexican muralist, Diego Rivera, who also affiliated with the Communist Party. Soul mates and lovers, theirs was a turbulent relationship. Twenty years her senior, with a demanding and successful career, Diego was repeatedly unfaithful to Frida, with one of the most hurtful encounters occurring between Diego and her beloved sister, Christina.

Jung (1925) explores how the unlived lives of an individual’s parents are carried in the unconscious and later activate the choice of a marriage partner, this ongoing influence of death in our lives. . Perhaps Frida and Christina enacted the competition, triangulation and betrayal that were interwoven in their family dynamics. Frida also enacted the family secret in her marriage to Diego. Her mother was betrayed by her husband’s secret adoration of his daughter. Frida was both betrayed by a family member, her sister, as well as becoming the betrayer with her numerous sexual liaisons after Christina’s affair with Diego.

After she learned of the affair, Frida chopped off her hair, which Diego loved, in an act of defiance. Reflecting her sardonic humor, at the top of this painting are the words of a popular song:

“Look, I used to love you, it was because of your hair, now you‘re pelona (bald or shorn), I don’t love you any more. “ (Zamora, 1990, p. 64)

Frida said: “you have ruined my womanhood through your infidelities” (Herrera, 1991, p. 152). Frida used the imagery of her hair as a symbol of her rage, attempting to severe her attachment to Diego. Her fury is palpable in her ugly man’s clothes, mutilated hair, and angry expression. Frida’s femininity had been sacrificed at Diego’s altar of infidelity. She begins to sever her dependent attachment to Diego and continues this severance the “Two Fridas, which we will revisit later. Frida did never entirely sever her relationship with her husband. Frida and Diego’s passionate, stormy relationship survived these infidelities, her seriously dangerous miscarriages, their divorce, remarriage and her faltering health.

Frida suffered tremendously with her inability to birth a child due to her accident. In this piece, she depicts her inner horror of not being able to bear a child, another reflection of the golden and bloody relationship she has with her body. Frida suffered greatly from her infertility. Yet, a compensatory resource grew in her with her attachment and dedication to her nieces and animals.

I feel a deep kinship with these painting about her loss of mothering. These paintings reflect my suffering and also inspired me to paint my own pain. Frida has been like a patron saint of infertile woman and couples. Through her art, Frida transforms pain into beauty and truth and then penetrates into our inner loneliness, thus universally bridging our experiences to hers.

Diego and Frida’s relationship was very complex. On one level, he offered an arena for the enactment of triangulation and betrayal, her early trauma, as well as recreating her bonds with an older male, first her father and then Diego. Frida had a sense of this in her remark,

“I suffered two grave accidents in my life. One in which a street car knocked me down…The other is Diego” (Zamora, 1990, p. 70).

Diego was a paradox for Frida, giving her life, death, and rebirth.

Their lives intersected in many ways even before they fell in love. Frida was a budding artist and politically active before her accident. She had a high school crush on Diego and taunted him, while he was painting this mural at her high school. She would call him fat and then run and hide to see his reaction.

After meeting him at party at which Diego shot the phonograph, Frida became attracted to his untamed and unpredictable manner, perhaps one that matched her own. Although a tiny woman, Frida’s personality was large, loud, vibrant and extroverted and could match his personality and size. Frida developed a stronger compensatory style of defiance after the accident. She would hide her vulnerability and pain with a strident, loud and adventuresome persona.

Even her appearance was unconventional; she declined to remove her facial hair and was known for her unibrow, small mustache, and for her flamboyant Mexicana-styled clothes. Diego was financially generous to Frida and her family with her medical bills, her father’s financial problems and her future medical bills. Even with the financial assistance, Frida’s mother was unsupportive of her daughter’s marriage to Diego. With deep fears for her daughter, Matilde said it was marriage between “a dove and an elephant” (Herrera, 1919, p.48).

Similar to her father, Diego was a great artistic mentor to Frida. He indirectly influenced her to leave her early European style and adapt a more Mexican colonial retablo style. Initially, she absorbed his cultural embrace along with his political idealism. As her journey of individuation matured, her culture, politics and sense of style increasingly reflected the Self.

Diego and Frida were comrades and bound by their commitment to Communism as well as art. In a sense as seen in this painting, they completed each other, finding their anima and animus in the other in their relationship.

Diego was Frida’s muse and supporter artistically. In his autobiography, Rivera said that Frida’s canvases

“…revealed an unusual energy of expression, precise delineation, character and true severity. They showed none of the tricks in the name of originality that usually mark the work of ambitious beginners. They have fundamental plastic honesty and an artistic personality of their own. They communicated a vital sensuality, complemented by a merciless yet sensitive power of observation. It was obvious to him that this girl was an authentic artist” (Rivera, quoted in Alcantara and Egnolff, 1999, p. 115).

He has often said she was a better painter than he was.

Frida painted her painful inner experience through realism, symbolism and surrealism always laced with her indigenous Mexican culture. She never liked these labels and said, “I paint my own reality” (Carpenter, 208, p. 79). In painting her internal reality of suffering, Frida, along with Jung and others birthed a new approach to art, later called Expressive Arts Therapy.

Frida lived a paradox. Always close to death and suffering with many losses because of her accident, she lived largely by celebrating life. With “Two Fridas,” she holds the paradox of her existence: The European and the Mexico Frida. She becomes her imaginary friend and companion again and expresses the capacity to love and be loved as the two Fridas hold each other hands. Frida is painting her psychic pain, of her exposed and wounded heart. She holds the duality of existence: the observer and the observed, the conscious Frida who ego is observing and the universal Frida who source is from the objective collective unconscious. With the joined hands, she has developed a strong ego/self axis, able to consciously manifest a deeper connection to the larger Self. This was also a death and rebirth in her art: the death of the European feminine, and a rebirth as a Mexican icon. Using Jung’s lens, Frida’s eventual transformation from the personal into an archetypal image stems from her rebirth as Mexican feminine icon.

“Rebirth is an affirmation that must be counted among the primordial affirmations of mankind. These primordial affirmations are based on what I call the archetypes” (CW, vol. 9i, par.207, p. 203)

With the little deer, she holds the ego and archetypal imagery in a deeper way. She is animal and human, the human who observes, and the animal that is wounded. Yet the animal is still able to move. Culturally, this type of symbolism is native to Mexico. Yet Frida takes it a step further in creating her mythos. She can hold her suffering as she moves in life. Frida’s powerful stance strengthens her as she struggles to live each day in pain (West, 1997).

Frida explores another duality inside herself: the tragic victim and the heroic survivor. Psychologically, she has developed the caring mother who is able to hold her pain and is hopeful. Frida painted this while her health declined. At this time, Frida was forced to wear a steel corset and was confined to bed. Holding this tension of opposites, she released her libidinal energies and through her art moved more into the archetypal realm as her pain increased. She is becoming a universal symbol of the Mexican Tehuana woman, connected to the earth while existing in the moonlight. The Tehuana garbed Frida holds the blood and golden colors of her accident in her dress now as fierce passion and regal majesty.

After Frida had her right foot amputated at the knee, she created this drawing that was discovered in her journal. In contrast to her other journal; this drawing is a complete, thoughtful piece. She depicts her greatest fear, the loss of feet and thus her independence. Frida created these feet as “Milagros,” a Mexican amulet whose name means miracles. Through the miracle of her art, she can accept this loss. Frida now lived in the archetypal realm of the imagination and can learn how to fly. The writing on the feet says “Feet What Do I Need Them for I have Wings to Fly” (Kahlo, 1995, p. 274).

Frida became very depressed after this surgery and lived increasingly in the spirit world, on the dark shadow side with alcohol and drugs, and on the other side through her creativity and connection to the spirits of Mexican culture. Her archetypal imagery emerged more and more in her paintings. Seen in tears in “Without Hope,” she vomits, expelling the horror of her suffering onto her easel. The earth reflects the fissures of her body, the violence done to her body and to Mexico.

This piece is a testament to her belief that art is medicine as she painted her suffering. This medicine led her to exist more and more in another objective reality.

With this earlier piece the “Two Nudes,” Frida turns to art to find comfort that did not exist in her external world. She is held by the feminine, a compensatory stance countering the rejecting personal mother. Her nudes evoke the transformation of her imaginary friend who waited for her in the center of the earth. Her friend is now her brown Mexican mother culture in nature, who holds her like a child. Both nudes could be the comforter and comforted. In the collective world, she can be vulnerable and comforted as well as loved by the mother. This piece may also reflect her bisexuality, receiving comfort from women when the masculine offers little.

With “The Love Embrace,” the earth and the Aztec goddesses cradle Frida. There is a union of darkness and light. She embraces the baby Diego, the passion of her life, mothering him now, while the earth mother cradles her. Frida identifies with the great mother. This is an incredible painting, bringing resolution of her personal pain with her mother, Diego, and her wounded body on an archetypal level. The emergence of the great mother flowing from her culture and her art provides the love and nurturance needed to bear the pain of her declining health.

In “Roots,” Frida is alone and lying down and she is one with nature. Frida is the artist whose creative urge lives in her like a tree and nourishes her. She is the artist rooted to nature. She is a numinous image of the artist who transforms her scars into the roots of life. This is an example of Jung’s belief of the transformative power of art. Frida is able to give birth not to a child but to the roots of life itself. All energies flow from a universal source of nature. This could also be the reversal of “Me and my nurse”. She now nurtures the archetypal earth.

Ironically, Jung discussed the artist with the same imagery that Frida used in this painting.

“The unborn work in the psyche of the artist is a force of nature that achieves its end either with tyrannical might or with the subtle cunning of nature herself, quite regardless of the man who is its vehicle. The creative urge lives and grows in him/her like a tree in the earth from which it draws its nourishment. We would do well, then, to think of the creative process as a living thing implanted in the human psyche.”

(CW, vol. 15, par. 115, p. 162)

In “Moses,” we see this interconnection and flow of life as Frida painted and as Jung espoused it. Frida painted this after reading Freud’s Moses and Monotheism. There is an unusual complexity to this piece. Frida said that she wanted to show “…the reason these people invent or imagine heroes and gods is pure fear. Fear of life and fear for death” (Zamora, 1990, p. 110). Frida may be imagining herself reborn into the collective. Fear and suffering propels us to create either with icons or art to comfort and soothe the fear of death and the suffering of life. Frida is birthed in the collective and welcomed, which is in striking contrast to birthing from the dead mother in “My Birth”

In these pieces, all created in the three years before her death, Frida was suffering physically. Her internal terrain changed as did her self-portraits. Frida related more to the archetype of life as depicted in nature. Her self-portraits, this empathetic mirroring and her imaginary friend were now fruit, foliage and animals, the archetypal source of life. As we can witness in this piece, “Sun and Life,” Frida’s paintings are full of life. On the shadow side, her paintings were said to be “over-exuberant,” due to her drug addiction. However, they also reflected the intensity one can feel about life with the approach of death.

In the year of her death, Frida returned to a human form for a self-portrait. However, this was not the human Frida or even a surreal Frida. This was the archetypal Frida. She stands straight and full-bodied. She is corseted with what could the tablets of the Ten Commandments. She no longer needs her clutches, so they fall away. The sun and the moon, the peace dove and the evil eagle surround Frida. She can hold the opposites and is strong and powerful, held by her political beliefs and universal hands. Frida is ready for death.

Only a few months before her death, Diego produced her first solo show in Mexico. Frida would not leave till her art spoke in her motherland and she fought to attend. Though weak, she obeyed her doctor’s orders not to leave her bed and had herself carried into the opening in her bed.

Frida died on July 13, 1954, 54 years ago, entering the collective world totally. She now lives through her art. Frida has become an archetypal symbol of the wounded yet triumphant feminine whose art become medicine. She embodied the sacred marriage of life and death through her paintings.

Long after her death, Frida, who turned 100 last year, continues to intrigue me. Twenty years ago, she invited me to her wounded table to learn from her. At this table, she confronted her pain, shadow and death and discovered meaning in her life. Unafraid of Coatlique, she danced with death and uncovered universal truths in her art. Frida’s dance with death was her greatest teacher and has been mine, and perhaps now, yours.

Frida caressed life as she approached death. The voice of her psyche spoke in her final painting, “Viva al vida,” “Long Live Life”!

Frida Kahlo References

Alcantara, I., & Egnolff, S. (2005). Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera.Munich: Prestel Publishing Ltd.

Beck, E. T. (2006). Kahlo’s World Split Open. Feminist Studies, 32(1), 55-81.

Calavera, R. Y. (2003). Dia de Muertos II. Mexico: Artes de Mexico.

Carpenter, E. (ed). (2008). Frida Kahlo. New York: D.A.P./ Distributed Art Publishers.

Chodorow, J. (1991). Dance Therapy and Depth Psychology: The Moving Imagination. New York: Routledge.

Dosamantes-Beaudry, I. (2001). Frida Kahlo: self-other representation and self-healing through art. The Arts Psychotherapy, 28, 5-17.

Downs, L. (2001). Border: La Linea: Narada World.

Fernandez, M. (1971). Frida Kahlo: “La mejor expresion moderna de la vida y el mundo plastico de una gran

Artista”: Departmento de Actividades Cinematograficas.

Frida Kahlo. (2005). On Biography: A&E Television Networks

Goldenthal, E. (2002). Frida Soundtrack: Miramax.

Granziera, Patrizia. “From Coatlicue to Guadalupe: The Image of the Great Mother in Mexico.” Studies in World Christianity 10(2): 250-273. 2005.

Grimberg, S. (2006). I Will Never Forget You: Unpublished Photographs and Letters. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books LLC.

Harding, M.E. (1970). The Way of All Women. New York:: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Herrera, H. (1983). Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo. New York, NY: Harper Perennial.

Herrera, H. (1991). Frida Kahlo: The Paintings. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers Inc.

Jung, C.G. (1961). Memories, Dreams and Reflections (with Aniela Jaffe). New York: Vintage Books.

_________. (1928). “Marriage as a Psychological Relationship” in Cary, H.G. and Cary, C.F. Contributions to Analytical Psychology. New York:

_______(1971). Psychological Types, Collected Works, vol. 6. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

________. (1959). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, Collected Works, vol. 9.1. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

________. (1968), Alchemical Studies, Collected Works, vol. 13. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

_________. (1963). Mysterium Coniunctionis, Collected Works, vol. 14. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

________. (1966). The Spirit in Man, Art and Literature, Collected Works, vol. 15. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Jimenez, V. (1997). Juan O’Gorman: Principio y fin del Camino.Mexico: Instituto Latinoamericano de la Comunicacion Educativa.

Kahlo, F. (1995). The Diary of Frida Kahlo, An Intimate Self-Portrait (B. C. d. Toledo & R. Pohlenz, Trans).. Mexico: Abradale.

Kahlo, F. (1995). I Painted My Own Reality. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books.

Kultur. Great Women Artists: Frida Kahlo: Kultur.

Kalsched, D. (1996). The Inner World of Trauma: Archetypal Defenses of the Personal Spirit. New York: Routledge.

Medina, O., & Gurrola, J. J. (1984). Frida: Naturaleza Viva: Veracruz.

Metcalf, P. & Huntington, R. (1991) Celebrations of Death: The Anthropology of Mortuary Ritual. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Cambridge University Press.

Paz, O. (1961), The Labyrinth of Solitude. Grove Press: New York.

Shore, A.N. (2003). Affect Dysregulations & Disorders of the Self. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Taymor, J. (2002). Frida: Mirimax.

The Life and Times of Frida Kahlo. (2004). On PBS Home Video: Daylight Films.

Vogel, S. (1995). Teotihuacan: History, Art and Monuments (D. B. Castledine, Trans).. Mexico: Conaculta.

West, J. J. (1995). Frida Kahlo: Dynamic Transformations. Proceedings of the 13th International Congress of Analytical Psychology. (95), 379-388.

Winnicott, D. W. (1965). The Maturational Process and the Facilitating Environment. New York: International Universities.

Yates, J. (1999). Jung on Death and Immortality. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Zamora, M. (1990). Frida Kahlo: The Brush of Anguish (M. S. Smith, Trans). Seattle: Marquand Books, Inc.

Frida Kahlo Image List

- The Dream, 1940

- Frida’s deathbed at Casa Azul

- My photo of Casa Azul, the home of Frida Kahlo, 2005

- Photo of Frida Kahlo, 1935

- The Dream, 1940

- My Photo of the Inner Courtyard and Garden of CASA AZUL, 2005

- Statue of Coatlique

- Thinking about Death, 1943

- Girl with a Death Mask, 1938

- Frida’s self-portrait: Diego on her mind, 1943

- My Family-Painting, 1950

- Kahlo childhood photo, 1913

- My birth, 1932

- My nurse and I, 1937

- The Two Fridas, 1939

- Frida in Coyoacan, 1927

- Portrait of My Father

- What the Water Gave Us, 1938

- My photo of “What the Water Gave Us” taken at the San Angel, Frida and Diego’s second home and studio, 2005

- Frida dressed as a male in a family photo, 1926

- The Bus, 1929

- The accident, 1926

- Clip from the Frida movie, the scene “The Accident

- Retablo, 1925

- Photo of Frida with her painted body cast, 1950

- Self-portrait: velvet dress, 1926

- Self-portrait of Mexican-looking Frida, 1929

- Self-portrait with thorns, 1940

- Four Inhabitants of Mexico, 1938

- Broken Columns, 1944

- Photo of Diego and Frida-younger version, 1928

- Frida and Christina, 1940

- Self Portrait with Chopped Hair, 1940

- Henry Ford Hospital, 1932

- Frida and the Caesarian Operation, 1932

- Older Diego and Frida, 1954

- Diego’s mural at Frida’ high school, 1922

- Self-Portrait with Loose Hair, 1947

- Self Portrait with Braid, 1941

- Frida and Diego on their wedding day, 1941

- Painting of Diego and Frida, 1944

- Self-portrait with parrot and monkey, 1940

- Frida painting the “Two Fridas”

- The Little Deer, 1946

- The Tree of Hope stands Firm, 1946

- Frida’s drawing of Feet from her journal, 1953

- Without Hope, 1945

- Two Nudes in the Forest, 1939

- The Love Embrace of the Universe 1949

- Roots, 1943

- Moses, 1945

- Fruit and Parrot, 1951

- Flower of life, 1953

- Sun and life, 1954

- Marxism Will Give Health to the Sick, 1954

- Photo of Frida at the gallery in bed, 1954

- Photo of Frida in her coffin, July 13, 1954

- The Wounded Table, 1945

- Vida al vida, 1954