By Ruth B. Skaggs

(Publish America, Baltimore, Maryland, 189 pages, 2004, $19.95)

Reviewed by Kate T. Donohue, Ph.D., REAT

Arts in Psychotherapy. Vol. 32(3), 2005

When the Persian poet Rumi talks about the “Beloved”, I experience the sense of an enveloping love. I had the same experience reading Ruth B. Skaggs’ Music: Keynote of the Human Spirit, as a reader, exploring her love affair both personally and professionally with music. Skaggs’ quotes a Sufi master that “…. the person who know the mystery of sound knows the mystery of the universe” and uses this as the goal for her book “…an attempt to explore the meaning of music in the whole of humanity” (p.11). It is valiant attempt in which she nearly succeeds.

The author provides a broad brush overview of the universe of sound from its beginning, including the theory of music therapy to its applications clinically, spiritually, archetypally and societally. This book is a wonderful book for interested newcomers to the world of music, and for beginning students in both music and expressive arts therapy. As someone who has studied various aspects of music therapy related to my work in expressive arts therapy, I found the broad-brush reviews only whetted my appetite and that I wanted to read more about the actual research studies.

The strength of this book is in the clinical application and case studies that the author provides. It is clear she is a seasoned clinician and her skill shines here. Skaggs focuses on receptive music processes and does not adhere to more behavioral approaches as many music therapists do, nor does she venture into the power of improvisational music. She presents receptive music processes similar to the Bonney Method of Guided Imagery through Music (GIM) and emphasizes the need for a deep understanding of the structure and impact of music on the human Psych and Soma. “ The person untrained in music therapy can do harm by playing around with a technique that reaches so deeply into one’s psyche” (p.29).

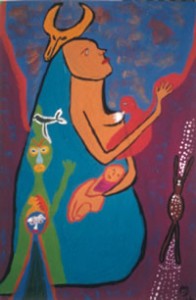

With her training evident in each chapter, the author recommends receptive music processes with which the reader could experiment. With each clinical topic, Skaggs also shares many small vignettes from her music therapy practice. There are two examples of very moving experiences in her clients’ lives with music that she shares with us. In chapter three, “The Archetypal Nature of Music”, she explores many archetypal symbols. One is the womb that seems related to the kivas of the Southwestern Native Americans as a place of safety and nurturing. This archetype, like music, holds the mothering function to envelop and comfort. Skaggs has a great deal of experience with music, imagery and addictions, and recalls a time when she worked with recovering addicts in treatment center. During a music and imagery process, a man experiences himself as “being in his mother’s womb. ‘I didn’t want to leave its safety. It is scary out there.’ Music provided a womb-like state (p.53).” Music and the recovery center became his womb, his safety and his first sense of self in his recovery process.

In Chapter 8, “Dying with Grace”, the author explores how music and its emerging images can help many patients face their fear of death and bring easier transition. A young man who was dying of AIDS was facing death with tremendous fear. Skaggs played Brahms Symphony Number 1, which brought the man face to face with his fear of death. She followed it by Mahler’s Symphony Number 2 (often referred to as “The Resurrection Symphony”). In this process, her client discovered a relationship to his spirit. “What a joke the universe has played on me. All this time I thought I was my body. Now I know it isn’t true. My body has been dependent upon spirit.” (p.141). He was no longer afraid of death and was grateful to his reconnection to his spirit. Here Skaggs embodies her strident recommendation that the therapist must have a firm grasp of the world of music in order to enter into these powerful arenas of emotion and “do no harm” (p.29).

I know Ruth Skaggs from her work with the International Expressive Arts Therapy Association and am familiar with her music based expressive arts therapy approaches. In her book, she mentions very briefly her work with visual arts and music. I would have appreciated a deeper theoretical and clinical exploration of her style of integrating other arts into her music-based practice. This would have made a great contribution to the expressive arts therapy field as well.

Ruth Skaggs has a profound love affair with music and shares this in her book. She feels that integrating music not only in therapy, but in education, medicine, and drug treatment, could help us with the “global changes we need for our survival” (p.159). With this short yet meaty book, she had made a very good case for the importance of music in our lives as well as providing us with rich clinical information and research. After reading her book, it is easy to understand why music is Ruth Skaggs’ “Beloved”.

Kate T. Donohue, Ph.D. REAT core faculty member at the California Institute of Integral Studies’ Expressive Arts Therapy Program in San Francisco.