The seeds for my trip to Africa were planted many, many years ago with my love for African art and dance.

In the spring of 1999, when I was 49, I had a mini-midlife crisis. I began thinking about my life and becoming half a century old. How did I want to celebrate it? The answer came to me very quickly: I wanted to dance in West Africa!

The seeds for my trip to Africa were planted many, many years ago with my love for African art and dance. Five years after attending an Expressive Arts Therapy symposium in Switzerland, I started to have dreams about African dancing. Soon after that, I found a dance class and embarked on what has become a passion for West African dance. In the spring of 1999, when I was 49, I had a mini-midlife crisis. I began thinking about my life and becoming half a century old. How did I want to celebrate it? The answer came to me very quickly: I wanted to dance in West Africa!

I decided to find a way to go to West Africa and dance for my birthday. Trips to West Africa are hard to find, but thank the god or goddess for the Internet. Here I found Aba Tours and a woman who spoke about travel as connection to the arts and culture. It was just what I wanted. When I talked to Ellie and told her about my dream trip she said, “No problem,” and gave me some ideas.

After many emails, calls, reading and talking to folks who had traveled to Africa, I decided to go to Ghana through Aba Tours. I knew this trip was a soul journey and I spent the next year reading, planning, dreaming, practicing my West African dance and getting excited about my adventure. My plans even garnered me a small mention in a Newsweek article on Baby Boomers at 50—my 15 minutes of fame!

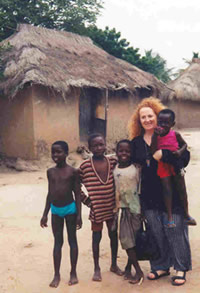

My husband and friends really supported me in my journey. When I asked for contributions of used clothes to bring with me to give to the people in the village of Kopeyia, where I would be staying, I received so many clothes I was able to bring two huge bags with me.

My descent into Africa started on my flight from London to Accra. I sat next to a very nice young man from Liberia, who had been living out of the country for the past ten years. He spent four years in Ghana and the last six in London for his studies. I knew about the coup and the changes in Liberia, but found that I was really naive about the toll of war. When I asked if he would ever go back to Liberia, the young man, John, turned to me. “My entire family was killed in one day,” he said, “I have no reason to go back.” My heart sank as I realized how different my American life was from Africa, where coups and economic winds are more extreme, and one’s life stability more vulnerable.

There were many ways to travel in Ghana. As a female traveling alone, I had decided to hire a driver/guide through Aba Tours. My driver, Rodney, emailed me a number of times before the trip, so he felt almost familiar and very welcoming when we met at the airport. It had taken about two days to finally get to Accra. It was dark at 8 PM when I arrived.

The ride from the airport gave me a sense of the teaming energy of Ghana. People were on the roadside selling everything you could imagine. Small shopkeepers with no electricity were open, their stalls illuminated with candlelight. The roadside seemed warm, mysterious from the candlelight and full of energy. I thought this is going to be different, and I was open to it all!

We found our way to the Beachcomber, in what I would later find out was Teshe-Nungua [a district/neighborhood of Accra]. I really had no idea where we were. The ride from the airport was along a busy road, then we turned off onto several dirt roads and arrived at a sweet little guest house with five small, thatched-roofed round huts. I felt very safe in Ghana. Our drive that night was mysterious but not threatening.

When I met Ellie, of Aba Tours, I really felt welcomed. I had talked and emailed with her so much, in my compulsive manner of wanting to be prepared, I felt like I knew her. We went to a little shop, had drink and talked. Aba, which is Ellie’s Ghanian name (Ghanaians are named for the day of the week one was born on), and I immediately connected and began to feel like soul sisters. Later I discovered Ghanians thought we looked like sisters. Aba had been a redhead in her youth.

I am glad I had one day in Accra to get to know the city. It was a whirlwind day with Aba and Rodney, meeting artists and art collectors like Baba, Bobo, Asante, seeing incredible carvings, kente cloth, fabric and markets. I had a short visit with Mercy Roberson, the stepmother of my friend Ken Roberson. Mercy seemed to have adopted me and thanked Aba and Rodney for all they were doing for me. I would spend time with Mercy and her family at the end of my trip, when I returned to Accra. I was so moved by the Kwame Nkramah memorial, having a taste of his vision for Ghana and Africa after reading his autobiography.

I rode shotgun through Makola Market, saw women from the December 31st movement at the National Theatre and ended the day at a multi-layered outdoor restaurant with live music and dancing.

The next day we were off to the village of Kopeyia, and I really had no idea what passage and surrender this experience would be for me. I had planned to spend nine days at Kopeyia. The first few days were very intense for with all the changes. There was no electricity, we used well water, had outhouses, no mirrors, no towels (I later got one), had wonderful Ghanian home cooked food and, best of all, individual dance instruction.

I started out with a great welcoming libation from the ancestors and then started my dance instruction in the Gahu, an Exe traditional dance that came from Nigeria and Togo and was modified in Ghana into a much faster version. There I was with four African men, three drummers and one dance instructor/partner. I had thought I knew a little about West African dance, but I was humbled. Not by the African men, but by my own western perspective. I really had not had a relationship with the drum, and Africans dance with the drum leading. Kojo and Emmanuel would tell me to listen to the drum, but I was confused. I was not clearly hearing the change in rhythms. I loved the movements of the dance and could see how fluid Kojo and Emmanuel were and how spastic I felt.

On the third day, I had a personal meltdown. I was trying so hard and shifting on so many levels that this was a clearing and letting go. I really felt something shift. I asked if in some classes I could dance with others. The Gahu is danced in a group. It is a community dance. Emmanuel, whom I grew to respect and really like, said “ No problem, we will have the children of the village dance with you.”

The children dressed in the traditional garments for this dance and gave me one performance so I could videotape it, then I joined in. The energy of the children and the community sense of the dance helped me feel the dance from inside. Then I really enjoyed the experience and learned the dance. Late one night, Gabriel, one of the villagers, did a libation to the drum. After that, I felt that I began to understand the voice of the drum and started to dance with it. On my last day, Aba’s group arrived during my afternoon instruction. Kojo would not let me stop the class. I continued to dance and the two Ghanian drivers with Aba joined in the dance. I received my biggest compliment from Gerry, one of the group members, who told me “You have proven that white people can dance.” The next day we had a class for the group and I could feel that I had the dance in my body and could see how much I had learned. I am not perfect, I will never teach dance, but I feel more freedom in my movements, I have a budding relationship with the drum and I danced in West Africa!

On the fourth day after my surrender to the drum I woke up at sunrise, as I usually did while in Ghana. A wonderful morning ritual woke me up. In the grays and blues of the sunrise, I could hear distant drumming and chanting, the crow of the roster and sounds of women sweeping. At that moment, I realized how much I loved this experience. I would never have this back home, and I would miss it. At that moment, I relished each morning as I slowly felt the ascent of the day and sound and hues of the morning. There is a Native American artist I really love, Helen Hardin. She has a painting called “Morning Brings the Abundant Gift of Life.” In Kopeyia, at sunrise, I had a much deeper sense of the abundance of the morning and the gift I was given in being there.

I experienced so many things in Kopeyia. My favorite was attending a funeral. Everyone said that in Ghana the best ritual is a funeral, so they found me a funeral to attend. Kojo, James and I walked into the fields of Kopeyia, on many paths, for forty-five minutes. I had no idea where I was, but I knew that they did. We came upon this small village, with no less than five hundred people in attendance at a funeral. People were dancing, drumming, and paying respect to the person whose body was sitting there with us. I danced and enjoyed every moment. I felt transported into another way of being with grief. I was so enraptured by the moment. When I saw Mamator from Kopeyia and she recognized me and embraced me, I was moved. I found Kojo and James again and told them how surprised I was that she had recognized me. They looked at each other and started laughing. At that moment, I realized what I had said. They were laughing because I was the only white person at the funeral so of course she would recognize me! Although I do not think about my skin color often, in that transcendent moment, I had forgotten the color of my own skin. I felt the interconnection of our humanity in an archetypal ritual of mourning, celebration and dance.